From the moment Melissa Mata was diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes three years ago, she found it impossible to keep her blood sugar in check.

Even after she was prescribed three different medications and lost weight through diet and exercise changes, her sugar readings remained stubbornly high.

Mata, 55, knew all too well the risks of uncontrolled diabetes. Several of her relatives have died at young ages from diabetic complications, said Mata, who works at the front desk of a University Health outpatient clinic in southwest San Antonio.

She was on the verge of a stage of the disease that she wanted to avoid at all costs.

“My goal was always that I never wanted to be on insulin,” Mata said. “I still don’t.”

When contacted by University’s research department about a study seeking to reduce or even reverse the effects of Type 2 diabetes through a new type of surgery, she was eager to participate.

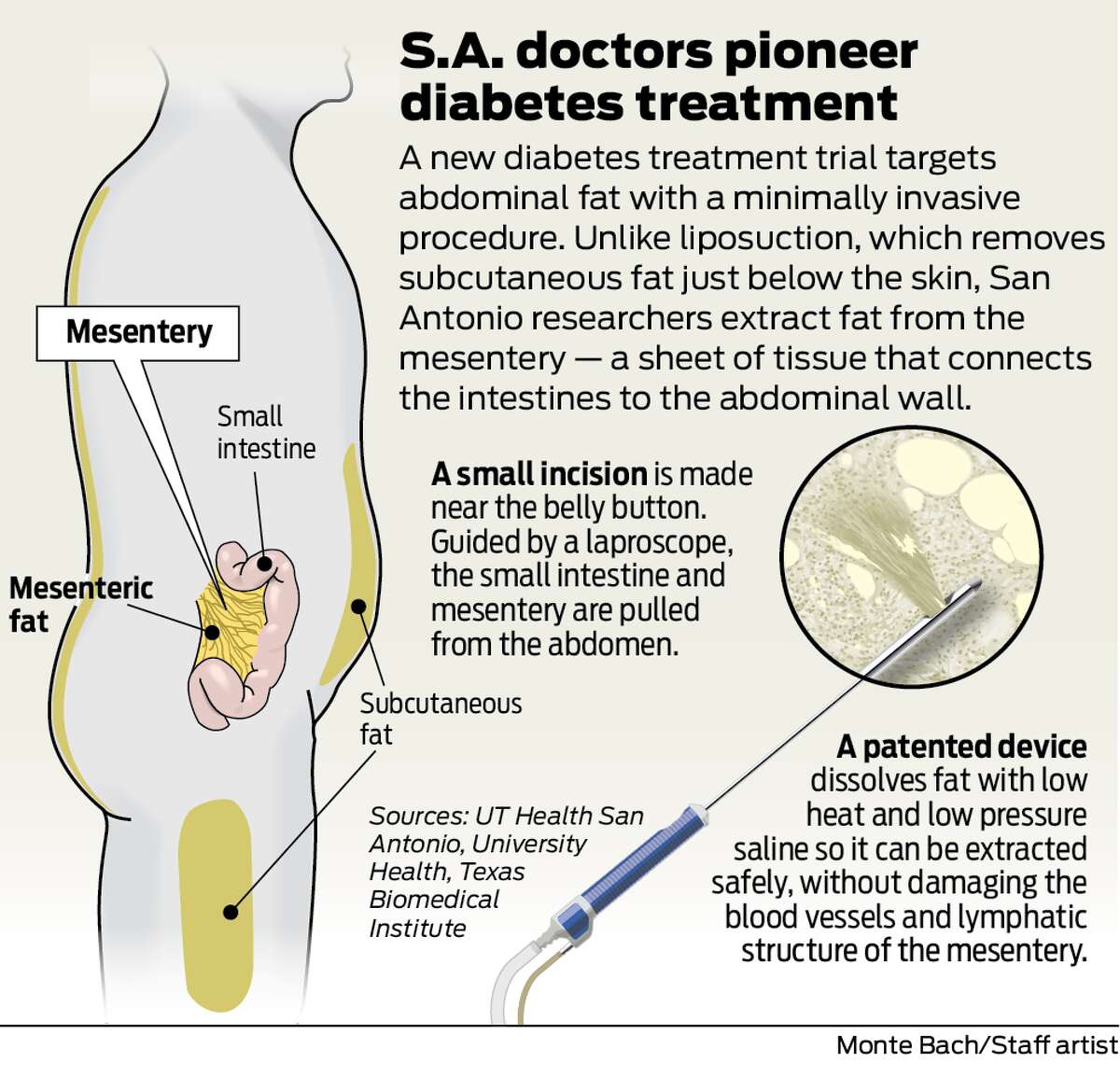

In late March, Mata was the second patient to undergo a mesenteric visceral lipectomy, a laparoscopic procedure where fat surrounding the intestines is extracted.

The technique was developed by researchers and physicians at UT Health San Antonio, University Health and Texas Biomedical Research Institute. The institutions were selected as research partners by Dr. Mark Andrew, a Pennsylvanian ophthalmologist who invented a device to dissolve cataracts that was later adapted for liposuction.

Diabetic patients who are interested in participating in the study can call the Texas Diabetes Institute's research line at 210-358-7200 and ask for Mary Samano.

A new way to treat Type 2 diabetes would have major implications for San Antonio and South Texas, where there are high rates of diabetes and complications from poor control of the disease, including amputations, kidney disease and dialysis.

In particular, diabetes disproportionately affects Hispanic communities, where the disease often is diagnosed in entire families due to genetics and other factors. Texas Diabetes Institute, a partnership between University and UT Health San Antonio, treats about 10,000 patients each year on the city’s West Side.

“If successful — which of course we’re very optimistic about — this would be a major advance for treating diabetes,” said Dr. Ralph DeFronzo, the study’s lead investigator and deputy director of TDI.

Fat surrounding the abdominal organs, known as visceral fat, is associated with a litany of serious health problems, including insulin resistance, heart disease and high blood pressure.

Researchers believe this type of fat secretes hormones and inflammatory proteins, DeFronzo said. An internationally prominent endocrinologist who heads up UT Health San Antonio’s diabetes division, he has studied causes of the disease for decades and invented a new class of drugs to treat it.

Doctors have long been able to remove the abdominal fat from just underneath the skin using liposuction. But until now, there was no safe way to remove internal visceral fat. That’s because of its proximity to the mesentery — a layer of tissue that affixes the intestines to the abdominal wall. It was only recently recognized as an organ linked to the body’s metabolic activity.

“There are lots of blood vessels that run through this fat, and you would tear them, and you would get a lot of bleeding,” DeFronzo said. “This new technique has a way of dissolving the fat within the intra-abdominal cavity, without causing any injury to the blood vessels.”

When patients undergo another type of laparoscopic surgery, known as gastric bypass, to reduce the size of their stomachs and reroute their intestines, their diabetes also often goes into remission, said Dr. Richard Peterson, a bariatric surgeon at University Hospital who is performing the operations for the study.

Most patients are able to stop taking diabetes medications just a day after surgery.

Weight loss plays a major role, but it is clearly not the only factor in diabetes, Peterson said.

Some patients do not respond well and see a recurrence of weight gain and the disease. And not all patients qualify for the bypass surgery, including those with lower body mass indexes.

The mesenteric study is open to people with BMIs between 30 and 40. There is an added benefit to operating on patients who are healthier, Peterson said.

“The metabolic fat is still active and causing problems, even if you’re not in that high BMI category,” he said.

The research will help shed light on the exact mechanisms at play with these procedures, Peterson said. Extensive laboratory testing is being conducted on the extracted fat to analyze hormones, enzymes and insulin growth factors.

Even so, he was a bit skeptical when he first began performing the mesenteric procedure on baboons at Texas Biomed, which maintains a large primate colony for research.

It did not take long for Peterson to become convinced they were on the right path. All eight of the baboons he operated on, six of which were formally included in the study, experienced remarkable improvements in their insulin resistance. A year post-surgery, the animals were still doing well.

“It was pretty shocking, pretty incredible,” he said.

In November 2019, Peterson performed the first procedure on a human, a man in his 40s.

The patient, Luis Calderon, had blood sugar readings of 400 to 450, even with medication. He regularly felt tired and suffered from headaches.

With the first patient, Peterson took a conservative approach, removing only 30 percent of Calderon’s mesenteric fat.

It will take more patients and data until the research team can quantify the procedure’s impact on diabetes, and how long its effects last. While the COVID-19 pandemic delayed the study, the research team is now looking to enroll a total of 10 patients.

If patients continue to respond well, DeFronzo said, it could become a noninvasive option for preventing complications and improving the quality of life for diabetics.

“We don’t want them going blind. We don’t want them ending up on dialysis. We don’t want them having heart attacks or heart failure,” he said. “If we get the blood sugar down into the normal range, this prevents all of these long-term complications.”

So far, the results have been promising.

After the surgery, Calderon’s blood sugar levels were reduced by half, to between 180 and 200.

Calderon, 46, said he viewed his participation in the research as a way to help current and future diabetics, including families like his where it has been passed down through generations. If it improves people’s lives, he said, it will be worth it.

Mata, who had 60 percent of her mesenteric fat removed, has seen even more dramatic changes a month out from her surgery.

Previously, her blood sugar was in the high 200s, at one point climbing to 499. Now, they are in the low 100s, reaching a maximum of 150.

Her appetite has changed, too. She becomes full faster and no longer craves sugar. Greasy and fried foods no longer sit well with her.

Mata expects to be weaned off her medications soon. She hopes the procedure can someday benefit her children and grandchildren, if they are ever diagnosed.

“For me, personally, it’s a lifesaver, because I never even thought I could get those numbers that low,” she said.

“You can change your life.”

lcaruba@express-news.net

"type" - Google News

May 01, 2021 at 02:03AM

https://ift.tt/3vuMO9u

Could removing abdominal fat reverse Type 2 diabetes? San Antonio researchers are testing a new surgery to find out. - San Antonio Express-News

"type" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2WhN8Zg

https://ift.tt/2YrjQdq

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Could removing abdominal fat reverse Type 2 diabetes? San Antonio researchers are testing a new surgery to find out. - San Antonio Express-News"

Post a Comment